This picture looks like it could be just an ordinary touristy snapshot. But it actually shows General Grant (left) and five officers on Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, after Grant whipped the Confederates in November 1863. Sticking out of Grant’s mouth is one of his ever-present cigars (which would eventually give him the throat cancer that killed him).

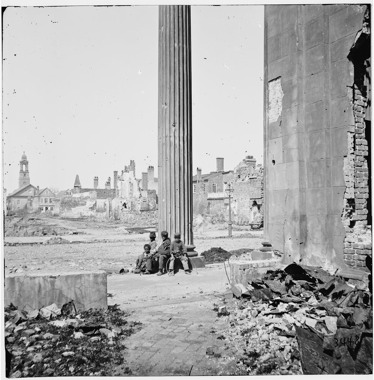

A quartet of black children wearing Army hats (at least they look like children) sit in the ruins of Circular Church on Meeting Street in Charleston, birthplace of secession.

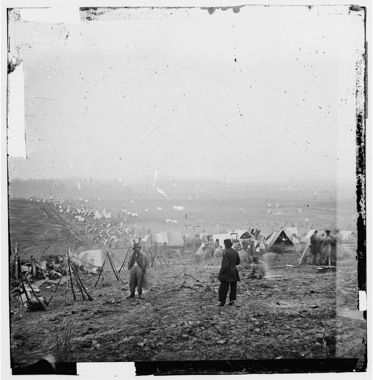

If the dating of this photo is correct, then it was taken during the Battle of Nashville, Dec. 15-16, 1864. It shows the outer edge of the Union lines.

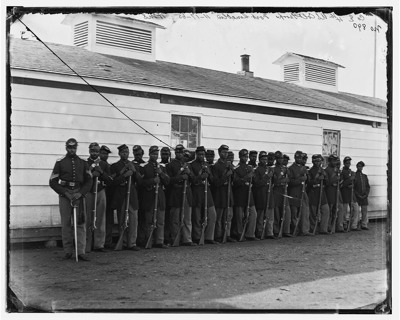

Men and noncoms of Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, Washington D.C. The bottom rail is on top, as these soldiers were among the 180,000 black men who served in the Union army during the war—and helped deliver ultimate victory.

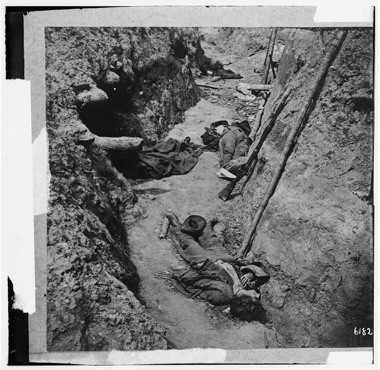

It looks like a scene from World War I, but this photograph shows dead Confederates in the trenches at Petersburg, Va., 1865.

Fugitive slaves crossing the Rappahannock River toward the North, August 1862.

This photograph shows what happens when an ammunition train goes BOOM! George Bernard saw the results when he photographed the remains of CSA General Hood’s 28-car ammunition train, which Hood’s retreating army burned after loosing Atlanta to Sherman, September 1864.

This was the late Shelby Foote’s favorite photograph because it “shows three Confederate soldiers who were captured at Gettysburg, You can see exactly how the Confederate soldier was dressed. And one of them has his arms up—like this—as if he knows he’s having his picture taken but he’s determined to remain the individual that he is. There’s just something about that photograph that strikes me as an image of the war.” (This remark appears during the episode on Gettysburg in Ken Burns’ The Civil War.)

At first, it seems like something of a happy scene, with many people standing around and what looks like garland decorating the tent. But that’s a surgeon’s saw the man at center is holding, and the original caption says the photo is showing an amputation.

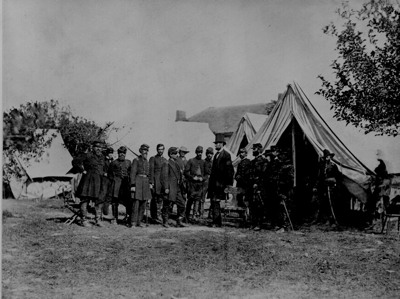

Alexander Gardener photographed Lincoln and General McClellan on the Antietam battlefield, October 1862. Notice how much taller Lincoln is compared to McClellan and his staff, and also notice McClellan’s strutting pose. McClellan styled himself the savior of the nation, but a couple of weeks after this picture was taken—and more than a month after the battle—Lincoln fired McClellan for good.

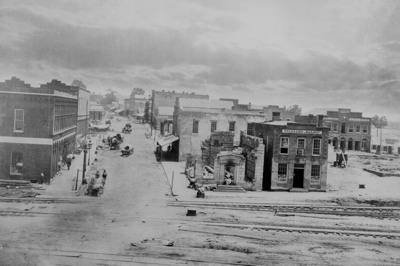

Peachtree Street, Atlanta, after Sherman captured that city in 1864. Looks a far cry from the glorious Technicolor splendor of “Gone with the Wind,” doesn’t it.

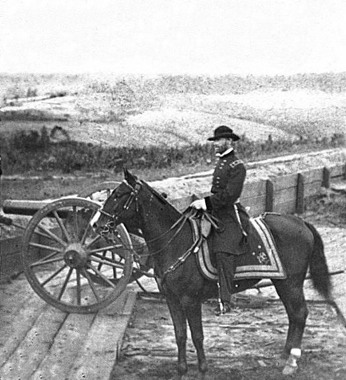

Most pictures of generals are stuffy and stiffly formal because of the nature of photographic technology at that time but George N. Bernard managed to capture this image of General William T. Sherman on his horse at Fort No. 7 before Atlanta, August 1864.

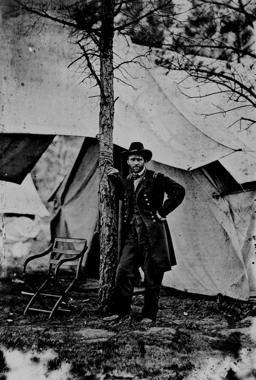

Timothy O’Sullivan took this and several similar pictures from the church, whose pews the generals are sitting on. At left, General Grant looks over the shoulder of General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac. In other pictures in the series, Grant is sitting on the pew facing the photographer. Put these pictures together and you have the closest thing to a movie that came out of the Civil War. Significant also because during this pause in the campaign, General Lee was getting ready to pull Grant into a trap at the North Anna River. But Grant sensed the trap and disengaged, sidestepping once more to the South.

It looks like a European town destroyed by artillery or bombers during either of the world wars. But this picture shows the devastating results from the fire that swept Richmond when the Confederate government retreated.

Lincoln’s remarks were very short, as the photographer had barely gotten ready when Lincoln was finished. Hence, the blurry nature of this historic event.

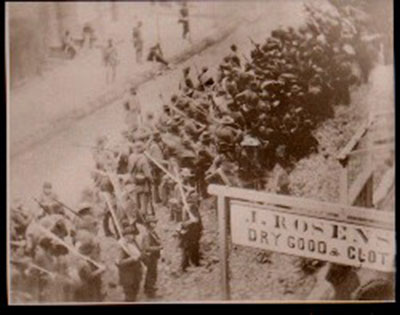

This remarkable photo of Union soldiers waiting to advance is usually misidentified as being taken during the siege of Petersburg, 1864-1865. The Library of Congress has it labeled as such. But according to James McPherson, it was actually taken a year earlier, before the Chancellorsville campaign.

James Gibson took this photo of a field hospital at Savage’s Station, Va., during the Seven Days campaign east of Richmond.

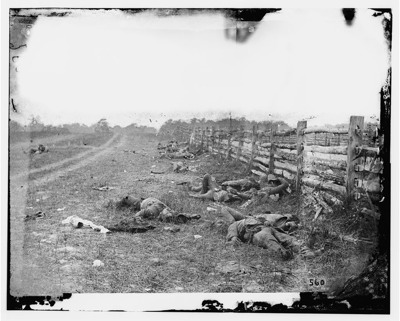

Alexander Gardener photographed these dead rebels of Starke’s Brigade of the Army of Northern Virginia where they fell along the Haggerstown Turnpike. Gardner took this picture two days after the battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg to the CSA). Gardener’s boss, Matthew Brady, took his photographs and made them into a display for the public—one that shocked people who had never before seen war dead (which was practically everyone).

This picture was taken a few days after his unfortunate assault at Cold Harbor. The strain on his face is palpable. By the time this photo was taken, Grant and Lee had lost a combined 80,000 men (50K Union, 30K Confederate) at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna and Cold Harbor.

This is one of the most historically valuable photos ever taken of the war because it is the only known photograph that shows Confederate soldiers on the march in enemy territory. (Maryland was indeed enemy territory to them, because slave-holding Maryland elected to remain in the Union.) What’s haunting about this photo is that, statistically speaking, before the end of the month one-third of all the men in that picture would be dead, wounded or missing. The photo is the property of the Historical Society of Frederick County (Maryland), and no larger size is available.