Whereas most of the other entries on this list made their money through racketeering, money laundering, illegal contraband sales, etc., Buchalter was the boss of “Murder, Inc.,” an organization of several thousand killers-for-hire who were paid regular salaries by the New York and Chicago mafias to hunt down and kill anyone who irritated them. Other members of this group were Meyer Lansky, Charles “Lucky” Luciano and “Bugsy” Siegel. After Buchalter was imprisoned for drug trafficking, he was sentenced to 30 years in Leavenworth, but then New York discovered that he was behind the murder of Joseph Rosen, a truck driver who refused to get out of town on Buchalter’s order. Buchalter ordered his men to hunt Rosen down and kill him. Abe Reles, to save himself, ratted Buchalter out, for this and four other ordered murders. Buchalter was given the death penalty for these crimes, and electrocuted on March 4th, 1944, three years after his conviction, the only major Mafia capo to be executed in the United States.

“Bonnie and Clyde” reveled in their own fame and took infamous photos of themselves, now called “the Joplin Album,” while they were in Joplin, MO. The most intriguing aspect of their career is that they fully expected to be gunned down at some point, and therefore intended to steal as much money, kill as many law enforcement agents and cause as much chaos as they could until then. Bonnie is not reliably known to have killed anyone during their legendary spree, but during each of their robberies, she was right in the thick of the fray – a 5-foot, 100-pound woman manning a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) with more muscle than an average man, running across country roads to their getaway car, sweeping the street and riddling police cars and shop windows until the gang was off. She did this all for Clyde Barrow, her unmarried lover. She was fiercely loyal to him, and is believed, but not proven, to be the killer of at least one of the gang’s 9 confirmed police victims, who had the audacity to shoot back at Barrow as he drove away from their Lucerne, Indiana bank robbery. Bonnie responded with a shotgun to his face out the rear windshield. She did not necessarily have a violent hatred of all law enforcement, but rather a hatred for anyone who threatened her love for Clyde, and she was described by almost all eyewitnesses as possessing an unsettling wide-eyed grin during their crimes. But she met her violent end, as predicted. More on that later.

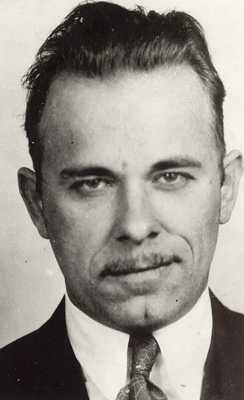

You might have expected Dillinger to rank higher, but this list’s entries are ranked according to the quality of nefariousness, not fame. Dillinger considered murder very inconvenient and tried not to hurt anyone. All he wanted was to steal the government’s money. He once shouted in a crowded bank, “Stay calm, ladies and gentlemen! We’re here for the government’s money, not yours! The government steals from you, so we steal from them.” During the Great Depression, this is precisely how much of the American public felt, and Dillinger was very smart for a criminal. He played the part of Robin Hood to be that much harder to catch, and it worked. Many poor, downtrodden citizens championed this handsome man with the gall to take on what Dillinger called, “the greatest collection of rip-off artists” of all time. Nevertheless, Dillinger stole for himself. He was greedy and wanted more, and no amount would ever have sufficed. He had a $10,000 bounty put on his capture, which, during the Depression, was almost enough money to set someone for life. He escaped from prison twice. The most amazing of these break-outs was from the Lake County Jail in Crown Point, Indiana, where his attorney sneaked a wooden pistol to his cell. Dillinger painted it black with shoe polish, and duped a guard into believing it was real. The guard let him out, whereupon he stole real weapons and escaped with four of his gang through multiple lockdown points, by holding all the guards at gunpoint. During his spree, from June 1933 to July 1934, his gang killed 13 lawmen, including both police and FBI agents. Dillinger’s involvement in these murders has never been reliably proven, but it is probable that he killed east Chicago policeman William O’Malley during a robbery of the First National Bank. From here on, J. Edgar Hoover wanted him dead, not alive. His death is well-known. He was leaving the Biograph Theater, 2433 N. Lincoln Avenue, Chicago, IL, on the night of July 22nd, 1934, with prostitute Ana Cumpanas, the so-called “woman in red”. She was dressed in an orange dress, but the lights cast a red hue over her as she walked out with him. FBI agent Melvin Purvis lit a cigar. Dillinger saw him, noted several other agents closing in and attempted to draw a pistol while running into an alley. He was shot three times, the fatal bullet passing through his brain from behind and exiting under his right eye.

The second half of “Bonnie and Clyde,” Clyde Barrow was the real motivation behind the gang. He was sent to prison at the age of 16 for stealing a car. While in prison he was raped almost every day by a sadistic inmate much larger than him, until one day Clyde got his hands on a steel pipe and bashed the rapist’s head in. This was his first murder, and it whetted his appetite. He harbored a seething hatred for the American legal system from then on, and once he was out, in 1932, he determined to make the law enforcement pay for his brutalization. During their spree, lasting from 1932 to 1934, Bonnie and Clyde robbed about 20 establishments, from banks to liquor and grocery stores to police armories. Clyde preferred the BAR, a fully-automatic 30-06 rifle, and Clyde, his lover and their gang did not hesitate to kill anyone – even innocent civilians – who threatened to stop them or slow them down. Clyde was described more than once by police and sheriffs as displaying a maniacal, open-mouthed smile while firing weapons at them during his escapes. Shop owners testified that he would laugh and scream in elation as he gunned lawmen down. His gang never stole enough money to retire. Their take at one robbery was 28 dollars, bread, milk, bacon and cigarettes, and one dead grocery store owner, Howard Hall. Clyde’s savage tour de force against all law enforcement was – in the public mind – in direct opposition to Dillinger’s honorable, Robin Hood persona, and roused the extreme ire of local authorities – especially the Texas Rangers. They enlisted the help of the legendary Frank Hamer, who had already been shot 17 times in the line of duty, and personally killed 53 people. Hamer was a professional tracker, and managed to pattern Bonnie and Clyde’s crime route, predicted where they would be, and set an ambush for them, on May 23rd, 1934, on a deserted, backwoods country road in Bienville, Louisiana. Six lawmen, led by Hamer, opened fire on Clyde’s car without any prior warning, killing him immediately with a bullet to the forehead. Bonnie was not so lucky, screaming in agony as the car was riddled with over a hundred bullets, not counting buckshot. Each man was armed with a BAR, a pump shotgun, and a pistol, and emptied every round at his disposal into the vehicle until it rolled past them, on fire, into a ditch. About 25 bullets were excised from each corpse.

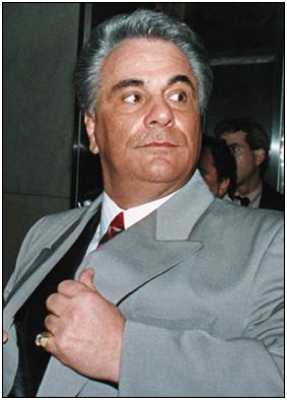

“The Teflon Don” based his entire career on the principle of keeping every crime he committed as secret as possible. But he made the mistake of flaunting his success at this in the face of the FBI, angering them to the point that they brought intolerable pressure on his enterprise. He got his nickname from the press after three trials resulted in hung juries or acquittals, despite massive evidence that he was guilty of everything from racketeering to drug trafficking to multiple murders. He was so powerful that he was able to order murders from jail while awaiting trial. The NYC public actually lived in fear of Gotti’s power, not that he would order a rampage on civilians, but that he was fully capable of making such a crime a reality, and had the temperament to do so. On March 18th, 1980, Gotti’s 12 year-old son, Frank, was run over and killed by John Favara, the Gottis’ neighbor. It was a complete accident and Favara attempted to apologize several times, sending flowers to the funeral. Gotti’s wife, Victoria, beat Favara over the head with a bat, prompting him to plan to move away. He was kidnapped on July 28th, 1980, by several men in a van, beating him with a bat and shooting him with a .22 silenced pistol. He was never seen again. Gotti is said to have boasted in prison to chaining Favara to a table in Gotti’s basement and cutting him to pieces with a chainsaw. Gotti died of throat cancer in prison, having finally been convicted of racketeering, five murders, loansharking, illegal gambling, obstruction of justice, bribery and tax evasion. He is estimated to have ordered the murders of over a hundred people.

Gillis may have had the most violent, fuming hatred of law enforcement of anyone in history. He loathed his nickname and is known to have rifle-whipped at least one man for saying it to his face. His partner in crime, John Dillinger, stopped him from killing the man, which would be a needless complication. Their partnership was confined to robbing banks. When Dillinger was killed, in July 1934, Gillis became Public Enemy No. 1, and the FBI’s entire Chicago-area field office came down on top of him. Gillis did not make the search a difficult one. He was so consumed with savage, intemperate rage against the police and “G-men” that, having killed one federal agent already at the Little Bohemia shootout, he initiated an audacious firefight with two cars of FBI agents in Barrington, IL, on November 27, 1934. Gillis did not have a habit of running from the police. He had a habit of chasing them. When a car with two agents spotted Gillis, his wife, and accomplice John Chase drive past, both cars did several U-turns, immediately firing at each other, with Gillis winding up in pursuit. The agents fled around a corner several blocks away, into a field, and waited in ambush, but Gillis’ engine had been shot through and he rolled to a stop in a park in the middle of the city. A second car of two more agents, Herman Hollis (who killed Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd) and Samuel Cowley, ran the criminals down and crashed into a gas station 100 feet past them. The agents exited their vehicle under heavy automatic fire from Gillis and Chase, while Gillis’ wife ran for cover. Both parties fired from behind their vehicles, until Gillis was fatally hit in the stomach. This made him irate and he stood up, walked out into full view of the agents and over 30 witnesses, and howled, “I’m going to kill you sons-of-bitches!” opening fire with a semi-automatic .351 rifle so quickly that bystanders thought he had a machine gun. Gillis was hit six more times by Cowley’s tommy gun, all in the chest and abdomen, but did not even fall down. He stood and continued firing until Cowley was dead from bullets to the chest and throat, whereupon Hollis hit Gillis with two rounds of 12-gauge 00 buckshot in the legs, nearly detaching his right calf muscle. Gillis went down, then astoundingly got back to his feet and shot Hollis dead. As he and Chase made their getaway, picking up Gillis’ wife, he told her, “I’m done for”. He died at 7:35 that night in bed, and his wife left him in a ditch to be found.

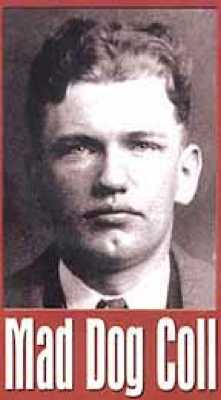

Coll got his nickname from NYC mayor, Jimmy Walker, after a shootout on July 28th, 1931, during which Coll attempted to kidnap a member of Dutch Schultz’s gang, Joey Rao. He did not sneak up behind Rao and blackjack him, or join with a couple thugs in dragging him into a car. Coll drove past Rao and opened fire on him with a tommy gun while he was standing in a crowd on the sidewalk. This crowd included children, one of whom, five year-old Michael Vengalli, was killed by four .45 bullets through his liver and lungs, which completely obliterated his abdomen and blasted his intestines into three children’s faces. Seven other children were seriously wounded. Coll actually pleaded not guilty to this crime, after none of the 40 or so eyewitnesses could work up the nerve to testify. The prosecution found one man who testified against him, but his testimony was destroyed by the defense when it was discovered that the “witness” was actually a professional witness for hire. Coll went free and smiled as he left the courthouse. This infuriated almost every Mafia family in New York. Dutch Schultz actually walked into a Bronx police station and offered a mansion in Westchester, NY, to the policeman who killed Coll. Coll was effectively on his own at this point, with flimsy ties, as a hit man to Salvatore Maranzano, until Charles “Lucky” Luciano had Maranzano killed. On February 1st, 1932, four men, probably sent by Schultz, broke into Coll’s apartment and killed two of his men and one bystander. Coll arrived 30 minutes late. One week later, on February 8th, Coll was on time to his own death. While placing a phone call at 12:30 in the morning, in a glass phone booth inside London Chemists pharmacy at 23rd and 8th Ave. Coll was busy extorting money from another gangster at the time, when a man with a tommy gun walked in and sprayed the phone booth for four seconds. This killer and his two accomplices were chased down the street by a passing policeman, but escaped. 15 bullets were excised from Coll’s corpse. The police never opened an investigation into his murder.

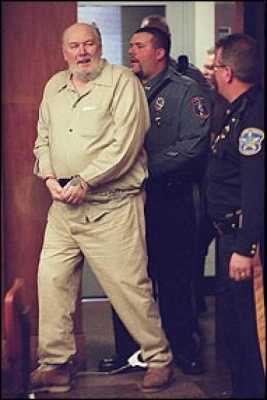

As much as this lister wanted to place him higher, Kuklinski was, quite frankly, a serial killer first and a mobster second. He might place higher on a list of serial killers, but anyway, it’s very difficult to crack the top two on this list. He was 6 feet 5 inches tall, 300 pounds, mostly muscle, and did not have a conscience to speak of. He committed his first murder at 13, avenging several beatings he had suffered from a teenage bully named Charley Lane. He surprised Lane on the sidewalk one day and beat him to death with a wood club, then knocked out all his teeth, cut off his fingers, and dumped him over a South Jersey bridge. He then stalked and beat the rest of Lane’s gang within an inch of their lives, bludgeoning one of them in the groin until his ruptured testicles were shredded by his shattered pelvis. Kuklinski’s extremely short, raging temper roused the attention of the DeCavalcante family of Newark, who hired him as a hit man. While working odd jobs for the family, he devoted his leisure time to stalking and killing random civilians, always grown men, in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan. His methods always changed, and thus the police could never draw a bead on him. He used guns, knives, his bare hands (“for the exercise”), cyanide (his favorite), strangulation, Molotov cocktails – anything that took his fancy as lethal. These people he killed in Hell’s Kitchen were total strangers to him, most of them street-walking bums not particularly missed by anyone. The police assumed they were killing each other. Kuklinski considered it perfecting his trade, since he was now working in the big leagues. He was first pistol whipped, then hired, by an underboss of the Gambino family, Roy DeMeo, who ordered to kill a random man walking by with his dog. Kuklinski did so without a second’s pause, shooting him in the head and kicking the dog’s teeth in when it snarled at him. DeMeo hired him on the spot and Kuklinski worked for the Gambino family for 30 years. He was finally caught by an undercover operation jointly led by the NJ State Police and the ATF. At the time of his incarceration, he claimed to have killed 200 people. Amazingly, the State of New Jersey did not sentence him to death on five counts of murder in the first degree, and even allowed the possibility of parole, albeit at the age of 110 (later adding 30 more years). He died in prison from natural causes on March 5th, 2006, at the age of 70.

His best friends called him “Snorky.” No one dared call him “Scarface” to his face. A born sociopath; he seemed smart enough to make it through high school at least, but could not control his temper and knocked out a female teacher when he was 14. That got him expelled and he grew up in NYC gangs from then on until he moved to Chicago in 1923, to work under “Papa” Johnny Torrio. He became Torrio’s best friend and worked his way up the ranks until he was in charge of the Chicago Outfit, which controlled all of south-side Chicago. All he cared about was making money, and most of it was made easily by means of illegal operations: prostitution, gambling, and especially alcohol. Alcohol was prohibited from 1920 to 1933, and this meant absolutely nothing to those who wanted their liquor fix. All Prohibition did was increase the crime rate and make people like Capone rich. But his sway over most of the speakeasies in south Chicago came at a price: he was the number one target of both law enforcement and outlaws (especially this list’s #1). He held his position as the number one gangster in the nation by means of severe violence. Anyone who crossed him had to be “whacked.” Not out of vengeance so much as a need to keep his throne, as it were. This is not to defend anything he did, of course, because all his violence against other gangsters, police, federal agents, and even civilians who crossed him, was motivated by supreme greed, and carried out under his legendary sociopathic temper. He ordered the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre against #1’s gang as a final act to put down his rival’s power and cement his authority throughout all Chicago. On February 14th, 1929, Capone retaliated directly against the North Side Gang by two hit men dressed as policemen entering the garage at 2122 North Clark Street, in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. Seven members of his rival gang were inside, but not the leader (#1). They assumed that the police were raiding them on suspicion of illegal alcohol, so they complied like always, expecting to be in and out of the police station in a few hours via bribery. Instead, the “policemen” let in two more gangsters in civilian clothes, and three or four of them opened fire on their unarmed victims from behind, while they leaned against the rear brick wall. All the murderers emptied 50-round drum magazines of Thompson .45 submachine guns into the seven victims, nearly cutting some of them in half. Two were amazingly found to be still breathing, whereupon one of Capone’s men finished them off with a 12 gauge buckshot, point-blank to their heads. One other example of Capone’s murderous sway over Chicago is the infamous baseball bat incident. The details will probably never be fully known, but Capone got wind of three of his underlings plotting to kill him and take over the Outfit. They were Joseph Giunta, Albert Anselmi and John Scalise. Capone invited them to a banquet in their honor, where they were held down while Capone beat them nearly to death with a bat. Some of his other men, later in life, testified that Capone did it all himself, then had them shot dead, and dumped on a road in Hammond, Indiana, south of Chicago. Capone died in 1947 in Florida, of complications from tertiary syphilis. The last anyone saw of him in public, he was fishing in a swimming pool, having completely lost his mind. Did you expect him to be #1? Well, read on.

You may feel cheated that Capone wasn’t #1, but this lister wasn’t merely throwing an arbitrary curveball. Moran was nicknamed “Bugs” because that was mobster slang for “100% crazy,” as in “crazy as a bedbug.” He was crazy because once he came to power as the boss of Chicago’s Irish North Side Gang, he showed absolutely no fear in provoking anyone into a fight. This was simply not smart, since mobster gangs considered themselves bound by oath to avenge all crimes against them. Moran once ordered a tailored suit, and when he arrived to pick it up the tailor quoted him what he considered an outrageous price, whereupon he broke the tailor’s arms and legs then walked out with the suit, paying nothing. Moran actually enjoyed ordering hits on people. Whereas Capone used violence and murder as a means to an end (making money), anyone who crossed Moran, no matter how slightly, was in imminent danger of being killed, whether or not it was bad for business. Moran is credited with popularizing the “drive-by shooting” as the quickest means by which to get rid of someone. You find out, from your informants, the building your enemy is staying in, and slowly drive by spraying the entire first floor with fully automatic Thompson submachine gunfire. The “Chicago Typewriter” fires a .45 ACP round, a heavy, full metal jacketed chunk of lead that can carry though thin brick walls, glass doors, furniture, people and the wood walls behind them. In nine months, from the summer of 1928 to spring of 1929, 618 gangsters of Moran’s North Side and Capone’s South Side were murdered on Chicago’s streets, most in the middle of the day by fully automatic submachine gun fire while pedestrians fled for cover. Capone and Moran were killing about equal numbers of each others gang, in addition to police and “government men”. Most of this violence was due directly to Moran, who liked the idea of wiping out all troublemakers even more than he enjoyed his illegal moneymaking. His war with Capone caused almost as much anarchy throughout Chicago as post-2003 Baghdad, Iraq. He personally kidnapped one of Capone’s most trusted bodyguards, hung him by his testicles with piano wire from a ceiling and burned his eyes out with cigarettes before the bodyguard’s weight castrated him. Moran dumped him off a bridge. He deliberately raided as many of Capone’s liquor shipments as he could find out about, just to enrage Capone. He liked hurting him however possible. On January 8th, 1929, just over a month before Valentine’s Day, he ordered a drive-by on Capone’s close friend and advisor, Pasqualino Lolordo. His death did not enrage Capone. It made him seriously depressed, and he attempted to arrange a truce with Moran. They met about a week later, agreed to turf boundaries, and less than another week later, Moran deliberately raided more of Capone’s liquor establishments, ordering his men to torture any Capone defenders and steal the goods. Two of Capone’s henchmen were present and fired back. One was killed, the other wounded. As he lay pleading in the street, one of Moran’s henchmen slashed him through the liver, and left him to bleed to death before an ambulance could be summoned. This was the last straw for Capone, who ordered the infamous hit on February 14th, 1929. His intent was to kill Moran, but Moran was late to the meeting, and as he approached the garage, the “policemen” walked in, diverting him to a coffee shop. He survived the attack and continued the war. It was not until Prohibition was repealed, in 1930, that the power of Moran and Capone began to wane. Capone was convicted of tax evasion (and nothing else), in 1931. Moran was in and out of prison until 1946, when he was convicted for mugging a bank courier. 10 years later he was released from prison, only to be re-arrested on the spot for a previous crime. He died in Leavenworth of lung cancer.