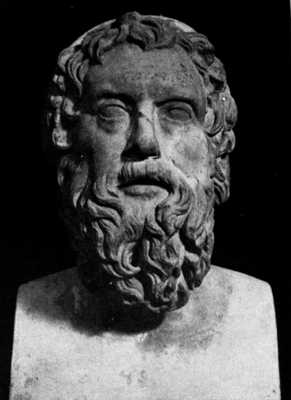

“You have all the characteristics of a popular politician: a horrible voice, bad breeding and a vulgar manner.” Classical Athens was a deeply political city, as you would expect from a democracy. In a democracy the voters like to be informed, and they like to laugh at the people in charge. Aristophanes was a master of comedic plays in Athens. Special festivals were held each year for comedy, and attendance was considered a religious necessity. A deeply conservative thinker, Aristophanes took aim at all the innovations he saw as dangerous. His targets included politicians (like the demagogue Cleon), the new thinkers (sophists, with whom he lumped Socrates) and fellow dramatists (such as Euripides, with his low born characters). His plays range from absurd situations (the search for the city of the birds) to the familiar (jury service), but all are packed with wit. Translation can be hard as his works are hugely topical and contain references we might miss. A good translation, when performed well, can still have people roaring with laughter and make a point. In the run up to the second Iraq War Aristophanes’ Lysistrata was performed world-wide as a call for peace. Aristophanes may have had the last laugh as at least some people, myself included, see the Lysistrata as an argument to see a war through to the end.

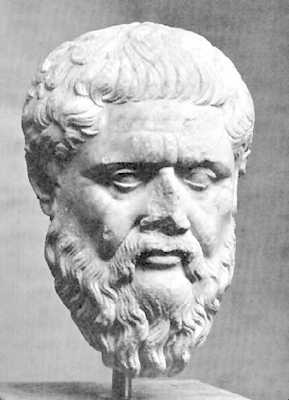

“I entirely agree,” said Aristophanes, “that we should, by all means, avoid hard drinking, for I was myself one of those who were yesterday drowned in drink.” Until I actually read the dialogues of Plato, instead of simply learning about them, I had no idea that Plato was hilarious. Anecdotes have a young Plato writing dramas before taking to philosophy. It would seem he never lost the knack for drama, or for mimicry. Plato satirizes all the way through the dialogues. Aristophanes is mocked in the Symposium as a boorish individual, who can tell an entertaining story but is incapable of deep thought. Plato catches Aristophanes’ backwards looking voice perfectly. In most of the dialogues, whenever Socrates, always a paragon of virtue, talks with someone, the other person is satirized. The interlocutor almost always misses the fact that they are being mocked, but we can hear the smirk Socrates was hiding. Plato uses satire to underline his philosophy of virtue so that those who may not be able to follow the philosophical thread of the dialogues may still profit from them.

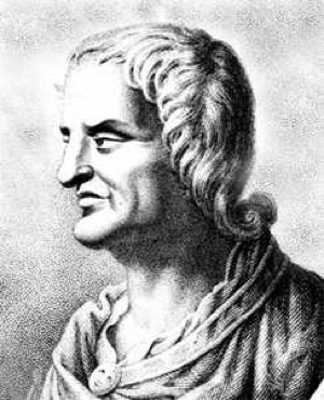

“Of all the Griefs that harass the Distrest, Sure the most bitter is a scornful Jest.” Like Athens, Rome was a political hotbed, and so satire flourished. Two styles of satire developed. The first is based on the works of Horace, who used poetry to gently point out peoples’ follies. The second, far harsher, was based on the poems of Juvenal. It is hard not to like Juvenal, even when he is at his most vulgar. His book of satirical poems begins with a lament; “It is hard not to write satire…” Like Aristophanes, Juvenal is conservative and attacks what he sees as moral decay. He mocks the people who fawn to the emperor, how hard it is to flatter effectively, female morals and people who lack common human feeling. Like many satirists, Juvenal suffered for his sharp tongue, being exiled for his wit. While his words were sharp they have become proverbial. We still say people long for ‘bread and circuses’ and ask ‘who will watch the watchers?’

“Ful del she sange the service devine, Entuned in hire nose ful swetely; And Frenche she spake flu fayre and fetidly, After the scale of Stratford atte bowe, For Frenche of Paris was to hire unknown.” Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is one of the greatest poems in English. It offers us an insight into the medieval mind and the social situation of a wide slice of society. By holding his dramatic mirror up to such an assorted group of pilgrims, Chaucer is bound to notice certain follies. We all recognize the social climber who tries to do as their betters do (in this case, speak French) and fails miserably (The prioress speaks French well, but with a heavy English accent). What makes Chaucer such a skillful satirist is that he spares no one their foibles, but he tempers his mockery. The knight is a good man and so the mockery is gentle, almost affectionate. The Pardoner, a man who preys on people’s fears of hell to make money by fraud, is scourged with all of Chaucer’s force. Knowing which targets are worthy of abuse is the satirist’s art.

“Wherefore farewell, clap your hands, live and drink lustily, my most excellent disciples of Folly.” Erasmus was one of the greatest minds of the European renaissance, and a founder of the reformation, famed for his learned collection and comparison of biblical texts. While Luther, the most dour man of the age, was inspired by that work, we take our inspiration from Erasmus’ ‘In Praise of Folly.’ In this short essay, written in the form of a speech by the goddess Folly, every folly of the age is held up for mocking praise. What makes this work so notable is that no one escapes the prodding satire. In the work the following people are mocked – the young, the old, women, those who have children, scholars, monks, kings, theologians… The list goes on. Since everyone takes their share of satire, no one feels hard done by and we all must consider; why do we do what we do?

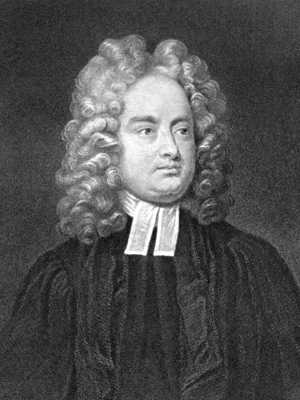

“It is computed that eleven thousand persons have at several times suffered death, rather than submit to break their eggs at the smaller end.” We leave the gentle satire of Erasmus now, for a far sharper satirical mind. Jonathan Swift is best known today for Gulliver’s Travels, but his writings are extensive. Gulliver’s Travels takes the form of a travelogue, where each of the places Gulliver reaches reflects, in grotesque form, some wrong of contemporary society. Gulliver feels morally superior to the tiny men of Lilliput, but is revealed inferior to the giants of Brobdingnag. The humor in Gulliver’s Travels is sharp, but nothing compared to the pamphlet A Modest Proposal. The proposal involved is one to solve the Irish famines, that occurred regularly, by the cooking and eating of babies. Even today, people are shocked if they do not understand the subtle satire.

“Optimism,” said Cacambo, “what is that?” “Alas!” replied Candide, “it is the obstinacy of maintaining that everything is well when it is hell.” Voltaire was one of the wittiest men in an age of wits. His Candide is one of the best books you can read in a few hours. It is the story of a young man, Candide, under the influence of a teacher of Optimism, Pangloss. Before the first page is over dreadful things begin to happen to all the characters. When asked why such things occur, Pangloss will explain “All is for the best in the best of all worlds.” The book may be seen as a narrow attack on the work of Leibniz, but in reality it is much more. It mocks the native optimism of youth, justice, Christian prejudice, war and class distinctions, as the deluge of disaster is dumped on the protagonists. What final advice does Candide offer us, who do not live in the best of all possible worlds? We must tend our gardens.

“Satire; Noun. An obsolete kind of literary composition in which the vices and follies of the author’s enemies were expounded with imperfect tenderness.” Bierce has divided opinion on his merits. Is he a vulgar and obscene cynic? Is he a keen and witty observer of human nature? His inclusion here tells you which way I come down on the matter. His ‘Devil’s Dictionary’ gives satirical definitions of words that, as well as making you laugh, make you wonder how much truth there is in his satire. The Devil’s Dictionary remains popular after a century, and is the perfect companion if you wish to puncture an enemy’s arguments. “Conservative; Noun. A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal, who wishes to replace them with others.”

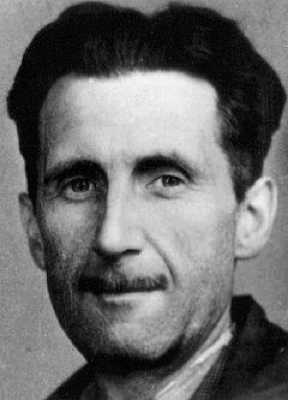

“All animals are equal but some are more equal than others.” The theory of communism is alluring. Who does not want to think that everyone is equal, and that utopia is just around the corner, if only we could learn to share? George Orwell, the product of an upper-middle class background and Eton, was deeply concerned for his fellow man, and toyed with communism as a weapon against fascism. His experiences in the Spanish civil war taught him that communism can descend into totalitarianism, purges and beastliness. So Orwell wrote a fable of communism, Animal Farm, to explain what evils it can lead to. In a few short chapters we see the rise of an idealistic idea to dominance, and the descent into a regime just as bad as anything that preceded it. The humor here is dark, but so were the times he was writing it in.

I do not know what quote to start this entry off with. A bit of a cheat, but these two have worked together to create a great satiric force. South Park has set its satiric sights on just about everyone in its fourteen years. The humor is absurdist and shotgun, no one escapes without having their ludicrous aspects exposed. Even though many view it as offensive, they seem to miss that everyone is getting their fair share of abuse. To watch South Park and feel you are being unfairly targeted is to reveal your own insecurities. Whatever your religious or political standpoints, by mocking all sides, South Park asks everyone to question their beliefs and accept nothing on the basis of an outside authority.