From the earliest ancestors, strange human hybrids, massacres, and memorial monuments, the dead can show unexpected rituals, DNA, and even peace when there should have been war.

10 Final Romanov Confirmation

The last royal family of Russia, the Romanovs, were executed in 1918 and hastily buried in shallow graves. The process of identifying Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, and five children took decades. In fact, it remains unresolved because not everybody agrees over the same test results. When the royal family’s bones were recently positively identified, one institution refused to accept the findings—the Russian Orthodox Church. The royal couple and three daughters were found in 1979 and interred in Saint Petersburg almost 20 years later. The Church never gave them a full funeral because they were unconvinced of the government’s findings that the remains were authentic. The other two children were found in 2007. In 2018, the Church ordered their own investigation and enlisted the help of geneticists. To do the tests, scientists had to exhume the father of the murdered tsar. Alexander III’s DNA and that of Nicholas II was a match; they were father and son. This could lead to the family finally being recognized and buried with full rites.[1]

9 Foreigners At Stonehenge

Stonehenge is one of the biggest Late Neolithic cemeteries in Britain. Some 56 pits once held the cremated remains of at least 58 individuals. In 2018, scientists chose 25 burials to determine their origins. Strontium levels (a signature based on diet) were mapped in each and compared to environments and dental material all over the United Kingdom. The result was startling. Ten were not locals and lived their last years nowhere near Salisbury Plain. A flag went up when several of the foreigners’ strontium signatures matched that of Wales. Stonehenge has one major connection with Wales—the bluestones. Stonehenge’s pillars came from a quarry in western Wales, almost 290 kilometers (180 mi) away. The bones roughly dated to when the bluestones were extracted around 3000 BC. These people could have been Welsh natives tasked with transporting the stones who perhaps died in Britain. Some appeared to have been cremated with wood from Wales. This means they died close to home and, for some reason, were transported and buried at Stonehenge. The discovery provided a rare look at a surprisingly vast network of traveling and trade, operating as far back as 5,000 years ago.[2]

8 Noble With Three Arms

Near the Bulgarian town of Primorsko, scholars got wind of a burial mound damaged by treasure hunters. Rescue excavations were launched to salvage the mound, which was magnificent in size and age. The 4,000-year-old grave stood around 7 meters (23 ft) tall and 100 meters (328 ft) in diameter. At first, archaeologists had to clear away pits dug up by the looters. In 2018, after everything was cleared, the team found a weird grave near the edge of the mound. Inside was a male skeleton. At almost 198 centimeters (6’6″), he was unusually tall for a Bronze Age Bulgarian. Red paint on the walls near the head and feet indicated power and noble birth. Despite this, his tomb was strangely empty. He only had a jar and dagger. It was apparently not the main grave, considering the placement of the tomb. Freakiest of all was a third arm, severed from somebody else and placed on the man’s left side.[3]

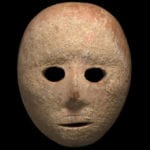

7 Peru’s Mystery Heads

In southern Peru, Vitor Valley has archaeologists stumped. A few years ago, 27 funerary pits were unearthed, each 3–4 meters (10–13 ft) deep. The remains of 60 people were brought to the surface and identified as likely members of the La Ramada culture. In 2018, things took a strange turn when six trophy heads were discovered. One still had a lock of hair thanks to Peru’s dry climate that turned several of the pit bodies into mummies. The presence of the skulls, severed after death, cannot draw a theory that satisfies all scholars. Ancient trophy heads in Peru are nothing new—people liked to hack off their enemies’ noggins.[4] What was different in this case was the possibility that they belonged to the community with whom they were buried. They might have been local warriors killed on a distant battlefield, and only their heads were brought home. They date from the same time as the mummies and skeletons, around AD 550, but only future laboratory tests can confirm if everybody grew up in the same place.

6 The Silo Massacre

During excavations in Alsace in northeastern France, archaeologists cleared 300 grain silos from the Neolithic period. These structures once stored grain and other food. A defensive wall around them hinted at a troubled region where resources had to be protected. This point was driven home in 2016 when the remains of 10 bodies were discovered inside one silo. They appeared to have died together around 6,000 years ago. There were six skeletons—five adult males and one adolescent—as well as the arms from four more men. Their hands, legs, and skulls had suffered violent blows. The most probable weapon was a stone axe swung with murderous anger. After they were slaughtered, the men were heaped on top of each other inside the silo. One theory suggests that the “victims” were actually attackers who died at the hands of furious locals defending their resources and families. Future genetic tests on the bones may reveal more about their origins. If they turn out to be from the Parisian basin, the raid story fits. People from that region eventually ousted the Alsace tribe around 4200 BC.[5]

5 Mayan Ancestors

In 2018, a team of researchers entered a cave in southern Mexico. Called the Puyil cave, it delivered an incredible find. Inside the dark depths, the remains of three people were seen for the first time in millennia. Ancient skeletons in Mexico are not uncommon, but the trio could be among the rarest ever found. It had everything to do with their ages. Two are estimated to be 4,000 years old, and the third died 7,000 years ago. This made them the earliest-known ancestors of the Mayan civilization. During their lifetimes, humans were moving away from a hunting lifestyle and began to settle in certain locations. However, the cave was not anybody’s home. There were signs of different groups visiting Puyil to perform rituals and bury their dead.[6]

4 First Egyptian Mummy

In 1901, an Italian museum acquired a corpse from Egypt that was supposedly found near the city of Gebelein. Curled into the fetal position, he was young, aged between 20 and 30. Until 2018, it was assumed that the desert naturally mummified the body. However, tests on the 6,000-year-old man found traces of artificial preservation. This made the so-called “Turin mummy” the earliest case of Egyptian embalming. In addition, the prehistoric morticians used similar ingredients to those found in the dynastic embalming recipe used 2,500 years later.[7] As the Turin mummy predates written language, embalmers likely preserved their knowledge verbally. Not only does it move Egyptian mummification back 1,500 years, it also shows that the practice occurred at other locations during the same era. The embalming procedure from the Turin case was also identified in funeral wrappings found 200 kilometers (124 mi) away from the city of Gebelein.

3 The Pommelte Victims

Near the German town of Pommelte stands a structure similar to Britain’s Stonehenge. Constructed of wood instead of stone, the monument has concentric circles of which the biggest measures 115 meters (380 ft) across. In 2018, excavations yielded a stomach-churning sight. The enclosure’s pits were filled with the broken bones of women and children. The battered skeletons suggested violent deaths, possibly as sacrifices. The absence of adult men and the disrespectful way that the victims were pushed into the pits made it unlikely that these people were killed by outsiders during a raid. There was no sign of a funeral held for murdered loved ones. Instead, the victims were buried with ritualistic and shattered objects. The 4,300-year-old site did have a cemetery, though. The all-male graveyard held 13 skeletons. Unlike the brutalized group, the men were buried in positions of privilege to the east of the henge. The site was used for nearly 300 years, and the male cemetery received bodies during different times. The last was buried around 150 years after the henge was destroyed in 2050 BC.[8]

2 Memorial For Equals

In Kenya, one memorial overthrows a major belief about the construction of early monuments. Previously, it was thought that rulers made the lower classes build megastructures (like the pyramids) as a way to dominate the populace. However, near Lake Turkana is a 5,000-year-old burial site that tells a remarkably different story. The people living there were going through tough changes. The lake had turned unreliable as a food source, and this nameless culture had switched to pastoralism. Usually, when resources are scarce and social roles are redefined, humans tend to fight. Instead, the herders built a monument together. Today, it is called the Lothagam North Pillar Site and contains a circular platform 30 meters (98 ft) in diameter. In the middle was a large pit, and over time, it was filled with an estimated 580–1,000 bodies. Every age group was present, and everyone received unique jewelry and equal burials.[9] The platform is also surrounded by pillars, cairns, and smaller circles. The community likely launched this multigenerational project to bond, get together, and create something lasting and familiar in a fast-changing world.

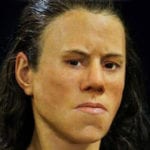

1 Unique Human Hybrid

In 2018, a 50,000-year-old bone was tested to determine the person’s ancestry. It came from a Siberian cave used by three human species—modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. The latter was an enigmatic people first discovered in the same cave years before. When they saw the results, scientists were so startled that they repeated the test several times. The bone belonged to a girl at least 13 years old who was born from a Neanderthal-Denisovan encounter. Her mitochondrial DNA, something only women pass on to the next generation, showed that her mother was Neanderthal.[10] This is the most direct proof of interbreeding between ancient human species. Apart from the teenager’s sensational genes, those of her parents also revealed fascinating tidbits. Her Denisovan father also had a Neanderthal ancestor but very distantly. The fact that he had Neanderthal DNA showed that his daughter was not the first offspring between the two groups. The mother’s genes were also a closer match to Neanderthals found in Croatia than to those in the Siberian cave. This indicates that Neanderthals often migrated between western Europe and Siberia—which spawns a mystery. Why did the two groups never fully merge? Experts just do not know the answer. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages