10 John And Christabel Russell

When post–World War I couple John and Christabel Russell were in the middle of their divorce, it was such a bizarre and lurid affair that George V was rather outraged that he had to read about it in the papers every day. He was so outraged, in fact, that British laws were changed to forbid the press from running coverage of divorce cases. In the years after the war, society belle Christabel married John “Stilts” Russell, heir to Lord Ampthill. Christabel was an independent woman who owned her own dress shop in London and who loved to go dancing night after night—and her wild social life earned her more than a few male admirers, even after her marriage. John, on the other hand, was the offspring of rather stuffy parents who solemnly disapproved of his bride. He was known as being something of a friendly pushover, and when he did attend parties, he was often dressed like a woman. In 1921, Christabel found out that she was pregnant. Although the news was first broken by a psychic medium, it was confirmed by a doctor, who also claimed that Christabel was still a virgin. The Russell couple immediately filed for divorce, with both parties agreeing on one thing: The marriage had never been consummated in the traditional way. With John often called away on military service, Christabel wasn’t precisely left on her own. Her family had already spent time doing damage control thanks to her many, many nights out with her many, many admirers, and when a baby entered the picture, they’d had enough. According to Christabel, her pregnancy came about one night when she’d found John sleepwalking, so she took it upon herself to consummate the marriage without him knowing. John claimed that the baby clearly wasn’t his, but with the doctors still proclaiming her virginity, there was an issue. She claimed that when he was awake, John made “Hunnish advances” toward her, giving her no choice but to refuse him. The verdict of the first court case was that John would be awarded the divorce he was looking for, and the baby would be declared a bastard. Christabel appealed a few years later, and since the baby was conceived while she was married, he was legitimate. Ultimately, her son Geoffrey would be named the fourth Baron Ampthill. The court case was, by all accounts, epic. Christabel testified that not only was she a virgin, but she had absolutely no knowledge of just what makes one no longer a virgin. Other claimed that it was likely that she’d simply had the misfortune to become pregnant by sharing bathwater with her husband.

9 James And Eunice Chapman

James and Eunice met in 1802, when she was an almost ancient spinster (at 24 years old), and he was a widower 15 years older. She accepted his proposal a few years later. That, of course, isn’t all there is to the story. Eunice claimed that James was an unfaithful, abusive drunk, and he claimed she was the abusive one. Ultimately, he left Eunice and their three children, all under the age of six, for a life with the Shakers. When James joined up with the Shakers, part of the deal was an agreement to give up the right to private property and other sorts of relationships—like the relationship that he wanted out of already. He did, however, want his children, and when Eunice wouldn’t agree to live with the Shakers, he took the kids and went into hiding with them. Technically, he was allowed to do so. At the time, children were considered the property of their father, and to make matters worse for Eunice, there wasn’t anything she could do about her situation. Even though her husband had kidnapped their children and gone into hiding, she still had only a few options when it came to reasons she wanted a divorce. Adultery was the usual claim, but even though she had witnesses who would attest to James’s infidelity, the Shakers were all about celibacy. Eunice’s only option was a mind-numbingly difficult one that got the attention of the whole country. In order to dissolve the marriage, she had to find a lawyer who would take her divorce petition to Washington, DC, in the hopes of getting an approval from the federal government. She ended up taking the national stage as a campaigner for her rights and the rights of other women. While some federal legislators dragged their feet in setting a precedent, claiming that all women would want a divorce if they let Eunice get one, she eventually got her divorce and custody of the children eight years after she married James. It only took a three-year court battle and the publishing of countless pamphlets about just what was going on in Shaker society. That wasn’t the end of the matter for Eunice. She ultimately got her children by going to New Hampshire and kidnapping them back, with the help of an angry mob.

8 Lord And Lady Roos

With the well-known drama surrounding the love life of Henry VIII, the power to grant a divorce shifted from the church to the crown, and in 1666, it was only granted with some pretty strict conditions. Those granted a divorce weren’t granted the right to marry again—at least not while the first spouse was still alive. The first time that changed was with Lord Roos (or Ross), earl of Rutland. Roos, known as being pretty harmless and rather inactive in the various committees that most nobility were privy to, was still kept away from home for a large portion of the time thanks to the necessity of travel. When Lady Roos ended up pregnant while her husband was most definitely away, Lord Roos filed for divorce, which was slightly trickier than it sounds, as their titles were inherited through her side of the family. After an incredibly scandalous trial, it was ruled that all of Lady Roos’s children were bastards, although there was at least one objection to the idea that they could still inherit through their mother. That was in 1667, and it was only in 1670 that Lord Roos received another declaration from Parliament—an approval to marry again. Roos appealed before the courts that he needed to marry again to produce legitimate children to ensure that his line wouldn’t die with him, and it was granted, but not out of any desire to preserve his family. Even though the clergy proclaimed that the idea of Roos remarrying and his heirs being legitimate was an affront to God, it was generally suspected that the ruling in Roos’s favor was made to set a precedent that might allow the king to divorce a wife and produce a legitimate heir with another one. The ruling was declared a triumph for the Protestant religion.

7 The Luxfords And The Clarkes

It’s a rather dubious honor, but just who got the first divorce in the New World is up for some debate. One thing’s for certain, though: We usually don’t think of early settlers as being too forward-thinking when it came to things like divorce. They were surprisingly more common than you’d think (for the time, at least), with Massachusetts and Connecticut averaging about one divorce per year throughout the 17th century. The Separatists were the first to allow divorce, and according to them, it wasn’t even a church matter; it was a civil one. Some say the first divorce in the colonies was between Denis and Anne Clarke, although other sources are pretty sure that they’re the second ones. In January 1643, the Court of Assistance of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay granted a divorce on charges of bigamy. Denis, who already had two children with Anne, left her, hooked up with another woman, and had two more children with her. Declaring to the courts that he had no intentions of returning to his wife, the divorce was granted, although Anne disappears from history with her win. In 1639, though, there are some fragmented records of a previous divorce, one that probably actually holds the title of the first. The wife of James Luxford appealed to the Massachusetts Bay Colony courts for a divorce, since he was also married to someone else. We’re not sure who made the ruling, but the courts not only granted the erstwhile Mrs. Luxford her divorce, but they also extended their protection to her and her children. Then, they unleashed their full wrath upon the man found guilty of bigamy. After fining him £100 (a large sum of money at the time), he was sentenced to confinement in the stocks for an hour during market day, and at the first possible chance, he was going to be put on a boat back to England.

6 Robert Devereux And Frances Howard

In 1613, Frances Howard appealed for an annulment of her marriage to Robert Devereux. Devereux, she testified, had not only been unfaithful many times over, he hadn’t been able to fulfill his marital duty when it came to her. They had been married for seven years, and with the marriage unconsummated, she said that it was null and void. Her claims were the talk of the Jacobean court, even more so because she already had plans for her next marriage, to Robert Carr. The big part of the problem was in the fact that Carr was a huge favorite of King James I and had no small amount of power when it came to court matters. The divorce became not just a civil or religious matter, but one of political power, maneuverings, and intrigues as well. With debate on the matter at a standstill, it was only with the intervention of James I that things shifted in Frances’s favor, largely because the king added a few more members to the commission who would vote in the appropriate way. Frances Howard got her divorce, and married the newly named earl of Somerset a few weeks later. Those who were against Frances were really against her. There were claims that she was both a whore and a practitioner of black magic and demonic witchcraft, the only explanation that some could find for her forwardness in appealing for something as scandalous as divorce. As for Carr’s part in the whole thing, his role is possibly even more scandalous. A former friend, Thomas Overbury, had spoken out on just how little he thought of Frances and what he thought of the whole situation. Supposedly, Overbury then committed some minor offense against the king and found himself whisked away to the Tower of London. Not long before the final verdict on the divorce was given, he died there. Few mourned at the time, and it wasn’t suggested until two years later that the newly married earl and countess of Somerset had a hand in his death, poisoning him to silence him in the matter of her divorce and their marriage. Carr had since been replaced as one of the favorites in court, and when the king ordered an investigation into the matter, the political machine refused to be stopped, even for a former favorite. Carr and Howard were both ultimately put on trial in 1616, found guilty, and sentenced to death. However, that sentence was reduced to imprisonment in the Tower and an eventual release in 1622.

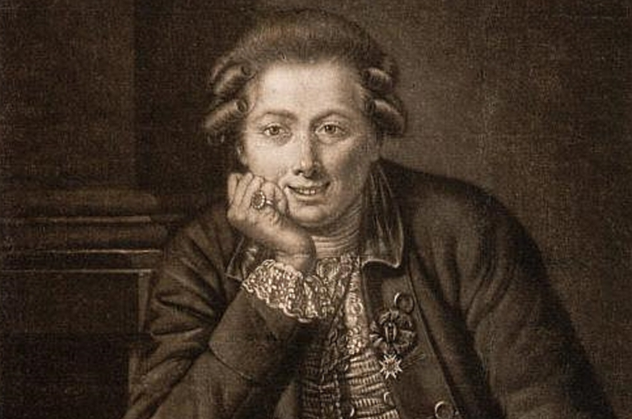

5 ‘James Howard’ And Arabella Hunt

In September 1680, James Howard and Arabella Hunt (pictured above) were married at Marylebone Church. The location itself would have been enough to raise more than a few questions for the lovers’ contemporaries. It was a remote place with something of a reputation. If two people wanted to get married and knew that there would be an objection from their friends, families, or other parties, they went to Marylebone. Two years later, Arabella Hunt filed a petition for an annulment based on a rather odd reason: James Howard was, in fact, a woman named Amy Poulter. In spite of the fact that there had been witnesses to the bedding ceremony, and “James” was known to regularly dress as a woman, the revelation threw something of a wrench in the normal workings of things. That was because Poulter had already been married when she married Hunt—to a man named Arthur Poulter. Witnesses testified that even though they had seen Poulter (or “James”) dressed as a woman, they had thought it was some sort of disguise. (No one seemed to wonder why.) According to some documents, Hunt actually left Poulter as soon as she discovered that Poulter wasn’t a man, although why it took two years for a divorce petition to be filed isn’t clear, either. As for Poulter, she testified that she hadn’t really been serious about the marriage, and she undertook it as a sort of “frollick jocular or facetious manner.” Witnesses also attest to knowing half of the couple as “Madam Poulter.” The court documents leave more questions than answers. Ultimately, the couple was given the annulment that Hunt had applied for. There are a couple of different suggestions as to just what her relationship with Poulter was. One is that their relationship was platonic and that they originally married so they could be buried together. There was a precedent for that in Mary Barber and Ann Chitting, who were married and laid to rest beside each other along with Mary’s husband, Roger. Another suggestion is that far from being deceived, Hunt was a gold-digger looking for any way to connect herself to Poulter’s considerable wealth, and when that didn’t work, divorce was the way out.

4 George And Caroline Norton

Caroline Norton was a crusader for women’s rights when it came to having a say in whether or not they were going to remain in a marriage. The granddaughter of playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Caroline was not only from a poor family, but she was outspoken and intellectual—all of which that a major turnoff for a 19th-century noble. She was finally proposed to, married at age 19 to a 26-year-old man whom she knew little about. George Norton, unfortunately, hated clever people, especially those who were more clever than him. While plenty of people were smarter than him, so was his wife. Within months, he had resorted to beating her to keep her in line, while they sank deeper and deeper into an impoverished lifestyle. Caroline began writing. At the same time, George was ordering her to mingle with some of the upper-class people her name allowed her access to. In doing so, she became popular within England’s political circles. At home, things got more and more violent. When she was pregnant for the fourth time, Caroline was beaten so badly that she suffered a miscarriage. The following Easter, Caroline went to see her sister. When she returned, she found the doors closed to her and her children seized. George had filed charges against England’s prime minister, Lord Melbourne, for “criminal conversation” (aka adultery) in the hopes of laying the groundwork for similar adultery charges against his estranged wife. The trial was over quickly, and Melbourne was found innocent. When Caroline tried to sue for divorce, she found that not only did she not have the right to sue as a wife, but because Melbourne’s trial had found Melbourne (and by extension, them) not guilty of adultery, there were no grounds to grant a divorce. George approached her with a separation agreement but quickly backed out of his side of the bargain, claiming that since they were still married, any contract between them was null and void . . . when it was convenient for him. After losing a court case where she appealed for financial protection from prosecution over unpaid bills (which were unpaid largely because George was still in control of their finances), she aligned herself at the head of a movement that would declare women as not equal, but deserving of equal treatment under the law—an important distinction. Ultimately, Caroline saw the passing of two groundbreaking acts—the Infant Custody Bill of 1839 and the Marriage and Divorce Act of 1857.

3 John And Willmott Bury

The 1561 divorce case between John and Willmott Bury featured a weird succession of events that demonstrated just how quickly an official verdict can be turned on its head. According to Willmott, her husband was impotent. A doctor’s examination seemed to back this up, along with an unfortunate accident before their marriage. John had been kicked in a bad place by a horse, leaving him with a testicle “the size of a small bean” and making him the butt of some rather graphic jokes once his difficulties made it to court. Based on the doctor’s exam and their inability to produce children, Willmott was granted her divorce. Both remarried, and unfortunately for them both, John’s second wife had a son. That’s when things took a turn for the rather weird. Whether or not John actually was the father of the child (there were rumors of adultery), English law declared that all children were the product of their mother’s husband. That meant that Willmott’s divorce had been given on false grounds, as John clearly wasn’t impotent, and they were never actually divorced. Their second marriages were declared void, and the child became a bastard and was officially removed from any sort of option to inherit. Eventually, the case was appealed by the child, and technicalities struck again. Since the second marriage had never officially been annulled, and John had only been declared to be still married to Willmott, it still stood, even though the first marriage had also been ruled to still stand. The case, which was subject to years of public ridicule, served to show just how complicated things can get. At the time, marriages could be annulled if there hadn’t been an official consummation. While women were required to prove their virginity (even though several noted physicians of the time were of the belief that the hymen was nothing more than a rumor), the Bury case serves to show just how far apart the requirements for a ruling in favor of men were from the ruling in favor of women.

2 James & Jessy Campbell, Edward & Jane Addison

There are few cases that show the inequality of 18th-century divorce law better than the sordid, incestuous story of James Campbell, Edward Addison, Jane Addison, and Jessy Campbell. At the time, the only reason for a divorce was adultery committed by the wife. One of the biggest sins of the era, it was seen not only as disrespectful, but as a tainting of the bloodline and the introduction of other, impure blood into the family. It perhaps wasn’t a great idea for the basis of a law, but it had worked for a long time, so it stood—until the messy affair of the Campbells and the Addisons. James Campbell petitioned Parliament for a divorce from his wife, Jessy Campbell. Jessy had been caught having an affair with Edward Addison, her sister’s husband. When James took his wife to court for her affair, he was immediately granted a divorce with little fuss. When Jane tried to divorce Edward, though, it started a long, drawn-out legal battle that was unheard of at the time. No English woman had ever been granted a divorce, and Jane would become the first to win her freedom from an unfaithful husband . . . eventually. A husband committing adultery simply wasn’t a big deal, and it was pretty much accepted. At that point, only four women had been successful in divorcing their husbands, and that was because they had leveled charges of bigamy and incest. The court case contained some heartbreaking revelations, including testimonies from the family maid as to the relationship between Edward and his sister-in-law. At one point, the maid testified that she found Edward in Jessy’s room, claiming that he’d made a mistake and simply opened the wrong door. The maid found this unlikely, because not only was he familiar with the house, but he wasn’t wearing any clothes. The adultery, which had already been proven in James’s divorce, forced the courts to rethink divorce in light of another generally accepted rule: Situations that were essentially similar demanded the same verdict. The case ended not only with freedom for Jane, but with the creation of the Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes.

1 Dorothea Maunsell And Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci

When Dorothea Maunsell filed for a divorce from Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci, it was for him not consummating the marriage, which, truthfully, was a given. Tenducci was a world-famous castrato. The Italian singer was born poor and subjected to a horrible, anesthetic-free operation when he was a boy, which removed his testicles to preserve his singing voice. Keeping his voice worked, and his career was already in full swing when he met the well-off Irish teenager Dorothea. When Tenducci fell in love with her, they went through the ritual of marriage, much to the disgust of her family, who soon literally took up arms, chased them across the country, and ended up seeing Tenducci in a Cork jail. After Dorothea attempted to use his connections to kick-start her own career (and failed), they eventually made it back to Italy, where they lived as a teacher and student. It was illegal for him to marry, and not long after, Dorothea met—and married—a businessman named William Long Kingsman. Back in Britain, it seemed like an open-and-shut case. God created marriage to create children, and there was no way for Tenducci to have children, so therefore, there was no marriage. But, relationships are never that easy, and rumors began to fly that Tenducci had children with the woman whom he occasionally introduced as his wife—and he did so by virtue of a third testicle. There was also some doubt as to whether or not the surgery had been performed right at all, with witnesses suggesting it might not have been done completely. Supporting that theory was the obviously normal growth of Tenducci in other ways. While other castrati had noticeably different physical features (namely obesity, very little facial or body hair, and spindly legs), he was pretty much normal. Things were complicated because there were undoubtedly children (though they probably belonged to Kingsman). Although Dorothea ultimately got her annulment, Tenducci became something of a poster child for the castrati. They were seen as deceptive, and they were not to be trusted. They were bitter, incomplete half-men. The outcome of the case was pretty different from the usual divorce cases involving female instigators. Dorothea regained her name and standing, married again, and could completely dodge answering the question of who the father of her children actually was. Read More: Twitter